'Django Unchained' Review: The sacred and the profane

With varying sensitivities to and understanding of the movie’s central character: slavery, Django Unchained was bound to stir up controversy. It was perhaps the film’s primary goal. But beyond stoking Spike Lee’s ire, Django’s, liberal use of brutality raises questions around what little is still off limits in the American psyche.

Django follows Inglorious Basterds and Kill Bill in Quentin Tarantino’s series of bloody revenge films. It tells the story of a newly freed, former slave Django (Jamie Foxx) on a journey to rescue his wife Broomhilda from slavery. Django is purchased and freed by Dr. King Schultz, a German bounty hunter who trains him to be the “the fastest gun in the South” as they make their way from Texas to Mississippi collecting corpses.

The first half of the plot unfolds like a 80s buddy film set to a Western backdrop, Lethal Weapon directed by Sergio Leone. It’s peppered with interesting performances, witty banter and satisfying scenes like when newly freed Django picks his own clothing for the first time, emerging in a blue satin Little Lord Fauntleroy getup. The audience also has a good laugh watching befuddled Klansmen stumble through the dark, unable to see through homemade hoods.

The film takes a sharp turn into dangerous territory, however, just as the pair does. Entering Mississippi, Django, Shultz and Tarantino begin the film’s real work of grappling with the savagery of slavery. The characters manage to navigate their mission. Tarantino gets lost. Unlike Inglorious Basterds and Kill Bill, where the director practices a deft touch, he loses all restraint with the flesh-mangling institution of slavery, rolling around in its gore like a pig in shit.

"There is something sexy about gallows humor,” Tarantino told the Los Angeles Times. This is perhaps the attitude longtime Tarantino critic Spike Lee anticipated when refusing to see the film saying it would be "disrespectful”to his ancestors. The New York Times’ review of the film proposes, “When you wipe away the blood and the anarchic humor, what you see in ‘Django Unchained’ is moral disgust with slavery, instinctive sympathy for the underdog and an affirmation (in the relationship between Django and Schultz) of what used to be called brotherhood.”

But wiping away the blood is easier for some than others and what causes disgust is just as complicated.

Sociomoral disgust, as defined by psychologist Carol Nemeroff, is a feeling of repulsion associated with the morally reprehensible and, like run-of-the-mill disgust, the sociomoral kind has the power to contaminate. “It is disgusting when there is a spiritual threat,” says Nemeroff. “A sense of horror at the idea of the evil person's stuff getting inside of you."

What left me cringing were the scenes where Tarantino loses sight of the “revenge” in revenge flick. So while the audience is spared Nazi death camps in Inglorious Basterds and the wedding-day massacre of Kill Bill, we’re allowed a front-row seat to bone-cracking, skull-crushing “Mandingo fights” in Django. We get to witness the bodies of slaves torn apart by dogs and cooked in torture chambers. Ultimately, the film’s major selling point: watching bad guys get what’s coming to them is polluted as Tarantino exhausts the permission for carnage that slavery affords him.

Understandably, it can be hard to determine the line when the film’s premise is a bloody romp through the Antebellum South but like pornography you know it when you see it.

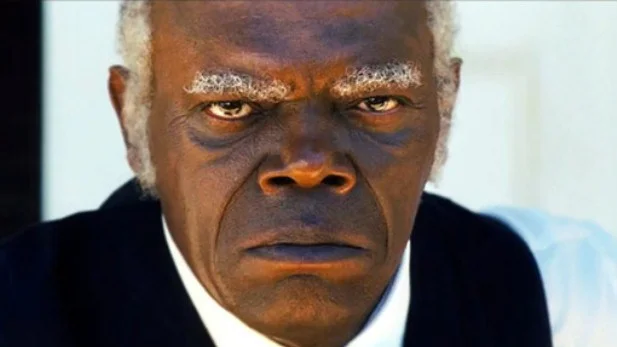

Luckily we’re spared some of the more debauched scenes from the script. Like one sequence where actress Keri Washington’s Broomhilda is auctioned, naked from the waist up, and sold to a young master who she eventually beguiles into a Jefferson/Hemmings relationship before being sold once more and subsequently chased naked by her new owner. In another, Django humiliates and beats Stephen, the evil head house slave, played by Samuel L. Jackson. I suppose someone had the taste to cut those scenes, keeping instead the film’s 100 plus utterances of “nigger,” but their stink still manages to linger in the celluloid.

Ultimately, with Django Unchained, Tarantino toys with a magic he doesn’t understand: a blend of images, symbols, memories and suggestions so dangerous that we usually tuck them away like Pandora's box or precede them with trigger warnings.