6 | The meltdown

At the end of last semester, Overton said she had “a major meltdown,” She actually refers to it as “THE meltdown.” “I wanted to be fired. I wanted to quit,” she said. “It was awful.”

It was a Friday, the last day of academic advisement that week. Overton said she hadn’t had a moment like it since her first year of teaching. Her 15 students came in with the usual commotion. The problem was that she had instructed them a few days earlier to whisper during advisement. At first she let them talk. When the announcements began over the school’s loudspeaker, she asked them to be quiet. This set one of the students off, she said.

“One girl in particular was like ‘you’re yelling in my ear.’ I wasn’t yelling in her ear, I was speaking loud enough for all of them to hear, I just happened to be near her.” Overton said that she should have just ignored it but the girl had acted out consistently in advisement throughout the semester, rolling her eyes and sucking her teeth whenever Overton would engage her. “I was finally like ‘Why are you being so mean?’ I think, at the point, I showed that it was feeling really personal for me.”

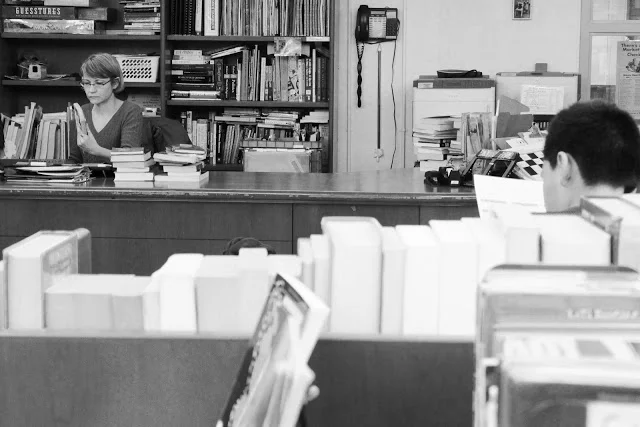

Minutes later, she said she could feel herself tearing up. “I put my papers on my desk and walked out of the class.” School rules dictate however that a teacher can’t leave a class unsupervised. Overton stood in the hallway outside the library door. “I could hear them in there laughing,” she said. So she waited until the advisement session was over and went to see Anna Hall. “I was crying in the principal’s office,” she said.

It’s not an uncommon scenario for teachers in stressful situations. Hall consoled her and Overton resolved to handle the situation head on. The next advisement session, she said the students were much more respectful. She talked to them and apologized for reacting in a way that “wasn’t helpful.” “I wasn’t apologizing for my emotions but for letting it get to me.” She said she wanted to demonstrate emotional maturity, that two people could disagree without being disruptive or disrespectful to each other.

Barely a month had passed since “the meltdown” when the same student who was so upset with Overton was asking for her help deciphering her transcript. She was the one shouting “Miss, Miss! This is messed up!”

Overton ignored the cacophony of voices, even the loud horn that sounds before the school announcements are made. She asked to see the girl’s transcript and walked her through it, assuring her that nothing on it was final. The girl seemed relieved. As the advisement session ended, she left with the others. There was not another “meltdown.” In describing what made that interaction possible, Overton said that the basis of her connection with her students is her fundamental belief that everyone starts off “really good.” She said the real work for all of us is trying to get back to the goodness and seeing goodness in others until they can see it in themselves.